Previous Interview with Stephen Wade

April 25, 2013

https://youtu.be/5ruL8dJirJI

____________________________________

New July 14, 2020 Interview

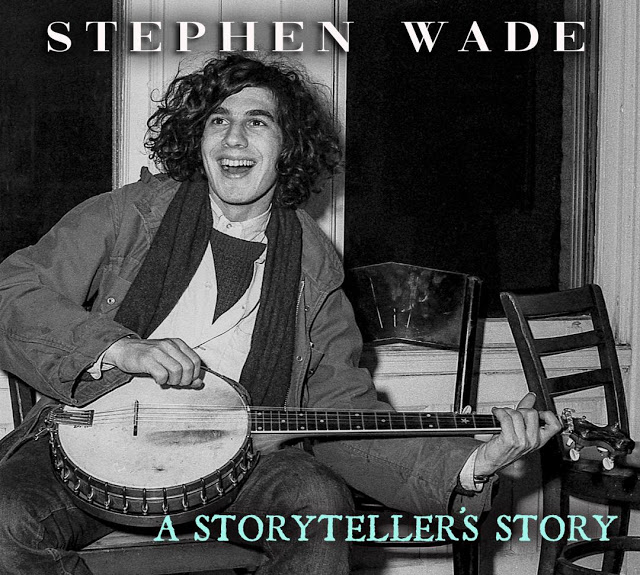

the album cover. Photo credit would be: © Ron Gordon

An Interview with Stephen Wade

Conducted by Joe Viglione

In a world where DVD and CD sales have fallen off and a new generation embraces the Internet and free music, musician/author Stephen Wade has put together a one-disc, information-packed description of the banjo with music and word that is absolutely essential. Lou Reed wanted to develop a “film for the ear” with his Berlin album, Wade has created an audio documentary chock full of intricate performance and authentic perspective with its release on the Patuxent Music label.

JV: Stephen, you and I were first in touch when you interviewed Bobby Hebb for your wonderful book The Beautiful Music All Around Us: Field Recordings and the American Experience (University of Illinois Press, 2012). The new album’s 44-page booklet is astounding and gives some of these answers, but tell our readers, what was the inspiration for the CD, A Storyteller’s Story?

SW: Thank you, Joe. The album marks the 40th anniversary of Banjo Dancing, a solo theater show that I wrote and performed. The show centered on spoken word pieces set to the five-string banjo, and accompanied by clog dancing and singing. Back in May 1979 Banjo Dancing opened in a small Chicago theater for what was initially scheduled a four-week run. But good fortune arose and that became a 57-week run, twice moving into successively larger theaters. After that, I performed it in other cities, among them Washington, D.C.’s Arena Stage. That booking, likewise planned for three weeks in full, turned into a ten-year engagement there, and Banjo Dancing became one of the five, longest-running, off-Broadway shows in the United States. Then, after finishing in Washington, I continued touring the show. In all, Banjo Dancing ran pretty much non-stop for nearly twenty years. Of course, it stays with me still, and its pieces have continued to appear in my concerts since those years. But they also figured in my work long before the show began.

This album, A Storyteller’s Story, whose subtitle is Sources of Banjo Dancing, focuses on precedents that led to that show. A couple of the tracks on A Storyteller’s Story appeared in Banjo Dancing, or else in its sequel, On the Way Home. But their role here, like the rest of the album’s contents, point towards persons and influences that set the show in motion. Behind it flows currents long present in American theater, music, oratory, and literature.

JV: What was “The Demo that Got the Deal” with Patuxent Records and how did you get the green light to put together such an in-depth project?

SW. Joe, I passed along your question to Tom Mindte, president of Patuxent Music. Here’s his reply:

TM: In 2014, I, along with co-producers Mark Delaney and Randy Barrett, produced The Patuxent Banjo Project, a compilation release on Patuxent. The album featured forty-one banjo players, all from the greater Washington / Baltimore area, each performing one piece. They were accompanied on the recording by several well renowned old-time and bluegrass musicians. Co-producer Mark Delany suggested Stephen Wade is a participant and I immediately agreed. That recording was the occasion of my first meeting with Stephen.

About three years later, Stephen approached me with a recording of a performance at the Library of Congress featuring himself and then recently deceased fiddler and folklorist Alan Jabbour. After listening to the concert, I agreed that is should be released. It came out in late 2017 on Patuxent, with the blessing, of course, of Jabbour’s widow Karen. So “the demo that got the deal,” was actually the previous release, Americana Concert: Alan Jabbour and Stephen Wade at the Library of Congress.

JV: How long have you been playing music – when did you start and what was your first instrument?

SW: I began playing this kind of music as a boy. I started out with a cherry red, single-pickup electric guitar to play the blues in as stinging a way as I could muster. At age eleven I became fortunate to have Jim Schwall of the newly established Siegel-Schwall Blues Band become my teacher. The band was just starting out, still several years shy of making their first album. Back then they were opening for a number of the great blues performers who had migrated to Chicago from the Delta. So I followed them around, as best I could.

I just loved watching the senior musicians play. I’d stand outside, listening near the doorway or watching through the front window of those taverns that I couldn’t enter due to my age. Those players included Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf, and Hubert Sumlin. I certainly didn’t catch all the cultural references embedded in their lyrics and intonations, but the audience knew. You could see this recognition, this joyful if sometimes sly communication passing back and forth between those great performers and their listeners.

Similarly, that mutuality, that sense of community understanding, arose in churches too, such as when Mahalia Jackson sang and the whole congregation swayed with her majestic presence. Again, I surely didn’t understand it all, but I found the experience so stirring. Moreover, this took place during the Civil Rights era. So much came together, this great art and the moral imperative of that period.

I think back, for instance, of the Staples Singers, and I remember that shimmering, tremolo guitar that Pop Staples played, its call coupled with the chiming response of his family singing back to him in refrain. They brought together sacred and secular realms so effectively.

My impressions from those years also include the great AM radio offerings; the sounds of that era’s popular music, from surf guitar to Motown to the British invasion, let alone the folk music revival in both its acoustic and electric dimensions. Of course, that era includes your dear friend, Bobby Hebb.

Every Saturday, after my guitar lesson with Jim Schwall, I’d hit the nearby downtown music stores. Sometimes the older kids tested out a guitar. They would plug in and play a riff from a hit song, I just thought that capacity as nothing short of Promethean. I wanted to do that too; to grab this music snatched from the airwaves, and translate it right then and there onto the guitar. I still feel that way.

JV: The sound quality on the disc is superb, how did you go about rounding up the tapes?

SW: Nearly all the album consists of newly made recordings. Its three “archival” pieces consist of a duet of Tom Paley and myself; another of Doc Hopkins and me playing for a Voice of America broadcast; and finally, for the album’s closing track, of my performing at Orchestra Hall, telling a story about growing up in Chicago. As for gathering these older tracks, well, they all were enjoying a quiet retirement, preserved on magnetic tape and shelved in a closet here at home, just slowly gathering dust.

I actually had forgotten about that VOA broadcast with Doc Hopkins, but once I put it on, I realized right away that I’d reached critical mass for this album. That formed the final part in the whole.

*****************************

JV: Did you record additional material specifically for the CD and, if so, where?

SW: It worked like this: I recorded most of the album by myself, playing live in a studio located in Springfield, Virginia, just outside Washington. I was fortunate in subjecting my performances to the evaluations that veteran producer Mike Melford provided from his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, just as I benefitted from the on-site impressions of engineer Mike Monseur who recorded me take after take.

Then, for those pieces where I planned to have accompaniment, Mike Monseur sent the final tracks on to Tom Mindte at his Patuxent Music studio in Rockville, Maryland.

There the other musicians contributed their parts, playing along via headphones to what I had done. I had certain accompaniments in mind, and talked about those combinations in advance with the players, visiting with them if possible, and playing through those settings. As it all unfolded, I kept conscious of both the particular songs, as well as imagining the album as a single entity; tallying it up as a unified listening experience

JV: Bear Family Records in Germany specializes in 1950s, early 60s, Doo-wop, and specialty genres. They’ve built up an audience of record buyers tuned-in to those styles of music that the label is known for representing. Does Patuxent have a similar marketing strategy?

SW: Again, Joe, your question here is best answered by Tom Mindte. Here’s his response:

TM: At Patuxent, we specialize in American roots genres. Bluegrass, old time, country blues, jazz, and recently, some rockabilly artists, are on our roster. We promote many aspiring young artists on the rise, as well as veteran musicians who still have something to say. As of this writing we have released 343 albums, most recorded at our studio in Rockville, Maryland.

The marketing strategy for all music is changing. As traditional sales tactics for music, such as sales of compact discs are drying up, new revenue streams are opening. There will always be those who are unwilling to pay for music. Since the advent of the tape recorder, folks have recorded radio broadcasts and concerts. Ironically, a large body of music that would have otherwise been lost has been thus preserved. The unauthorized use of intellectual property can’t be stopped, so we have to rely on honest music fans to keep us afloat. One new revenue stream that has been a great help to labels and artists alike is subscription radio, such as Sirius/Xm. A portion of the subscription fees paid by their customers is passed on to artists and labels. Income from that source has, in the case of Patuxent, been more lucrative than traditional hard-copy album sales.

JV: Are there libraries and museums that cater to Americana that help spread the gospel of the banjo…and do you perform at some of them?

SW: There are any number of institutions that embrace traditional music, be it the Bluegrass and Old Time Music Program at East Tennessee State University in Johnson City, or the Old Town School of Folk Music in Chicago to name but two. Interest in this music surfaces throughout the country. I don’t really think of myself a banjo evangelist, but there’s no denying its signal role here.

Most recently, that is, shortly before early March when everything shut down due to the pathogen, I did an album release concert here in Washington at the Institute of Musical Traditions. It was a wonderful night. I played two ninety-minute sets anchored in this community’s history and just built out from there. I put together a slide show that I coupled with narration, which in turn, framed songs, stories, and tunes related to A Storyteller’s Story.

Here’s a description of another such show I’ll do, pathogen permitting, next April. Originally, it would have happened this past spring. Again, I’ll center the program in historical circumstances unique to that locale and proceed from that point outwards:

https://www.oldtownschool.org/concerts/2020/04-11-2020-stephen-wade/

JV: Where do you find the most responsive audiences to the music that you love?

SW: That’s always a surprise, and ever shall it remain so. I don’t ever know ahead of time who may be most responsive, and I welcome that unpredictability. My job lies in finding the audience wherever they might reside. As my late friend, singer-songwriter Steve Goodman, once told me, “It’s not their fault they came.” So in that wry insight so characteristic of him, Steve taught me something both important and unforgettable.

I often localize my concerts, drawing, if only glancingly, on histories specific to a given place, and in that sense, bringing topicality to the material. But the larger need to somehow find a route from the stage to those seated in the house marks the performer’s principal obligation: to invite interest, and if to instruct, then as Alexander Pope enjoined, then also to delight.

All those years of Banjo Dancing demonstrated, at least to me, that it centered not just on the content of the work, but its communication. As my late director, Milton Kramer, repeatedly told me, “Entertaining is an honorable profession.”

JV: As we revere some of the great musicians that have played and recorded, what do you think people 200 years from now will think of this package? Historical, new and exciting, or both?

SW: Joe, you’ve asked a question that I cannot answer beyond addressing my own work within the album, of knowing what went into it. I can’t speak of the album’s reception now, let alone 200 years from now. That lies for others to judge, but I can take responsibility for its contents and crafting.

I see this album as a whole, as something that unites its audible parts with its written dimensions. As you know, there’s a variety of sounds present here, stemming from the songs, singing, arrangements, and monologues. It also includes some older pieces recorded in years past. Taken together, it’s my hope that the album notes, both the opening essay and the song annotations that follow it, set these performances in context, identifying their larger frameworks.

JV: How was the 1979 day at the White House and what transpired?

SW: Soon after Banjo Dancing opened in spring 1979, the American Theatre Critics Association held their annual meeting that year in Chicago. That this gathering even took place came entirely as a surprise to me and was certainly unanticipated. One upshot was that the lead reviewer in Time magazine attended the show and wrote it up. That life-changing review in what was then America’s biggest magazine made its way to the White House. One of the pieces the critic mentioned was my performance of the second chapter of Tom Sawyer, when Tom cons his friends into whitewashing the fence. In that fabled scene, Tom finds a way to transform the drudgery of work into the liberation of play. It also includes a passage where his friend Ben pretends to be a steamboat.

For the Carter White House, soon to voyage on the Delta Queen, and looking ahead to a Labor Day event to be held on the South Lawn with a thousand of the nation’s labor leaders and their families, that Time review of Banjo Dancing apparently combined themes already present. As I understand it, Rosalynn Carter read the piece and that set it everything that followed in motion.

The White House got in touch with my office and then sent Gretchen Poston, who served as the Social Secretary of the First Lady, along with two other staffers, out to Chicago to see me play. Essentially I think they wanted to confirm what the Time review had claimed on my behalf. At that point, literally right after the show they attended, the plan sealed. I would fly out to Washington after my Sunday night curtain on Labor Day weekend in order to play the next day at the White House. By then Hurricane David hovered near Washington, but fortunately it never made its way there.

That night, September 3, 1979, President Carter addressed the crowd and then introduced me. I played several pieces, including the White House’s request that I do that Tom Sawyer whitewashed fence excerpt about work and play. It fit the Labor Day theme as well as implicitly recalling the steamboat trip the First Family had recently taken. After that, I played another set of tunes, and so the evening ended.

The President then called for me to meet him and the First Lady. He told me how they’d been reading Huckleberry Finn to Amy, their daughter, at bedtime. They were most warm and friendly.

The whole experience remains unforgettable. My dressing room had previously been used by President Roosevelt during wartime, and I remember its furniture included Thomas Jefferson’s ink pot and writing set, and a highboy that had once belonged to Benjamin Franklin.

All kinds of tiny dramas as well as delights arose. These included my main banjo’s head having broken overnight while flying in, requiring me to play my back-up instrument for the performance. That really was not an ideal time for something like that to happen.

Yet even more I remember after a mid-morning sound check, just wandering on the White House’s South Lawn. Members of the National Park Service were putting up picnic tables, and they said I could walk around. I looked at the Washington Monument from an angle I knew I’d never see again, and just for those moments, that beautiful view and that feeling I had roving those hallowed grounds—this stays with me.

JV: Your work is so in-depth that I am totally impressed with the detail. What do you have planned next?

SW: Well, I’m writing another book. Apart from that, I continue learning new songs and work on my playing and singing. In fact I’ve got a singing class today. I just hope my teacher won’t squelch the volume during our Zoom session. I’ve got two hours of brand new old songs to play for her.

Thank you for your time, Stephen